Over the last month I dived into the fascinating field of Machine Learning. My motivation was to learn about some of the cutting-edge methods used and developed by research labs and tech companies around the world. As I was looking for an original and challenging use-case to take on, I thought of creating an application that could recognize an airliner’s make & model from a simple photograph (similar to this car-spotting application). This article describes my attempts and results.

My source code is fully available on GitHub. Feel free to have a look, test it with some aircraft pictures and give me some feedback!

About Machine Learning

Machine learning is a subfield of computer science that evolved from the study of pattern recognition and computational learning theory in artificial intelligence (Wikipedia).

There are various reasons why this is a field of utmost interest, especially for technology startups.

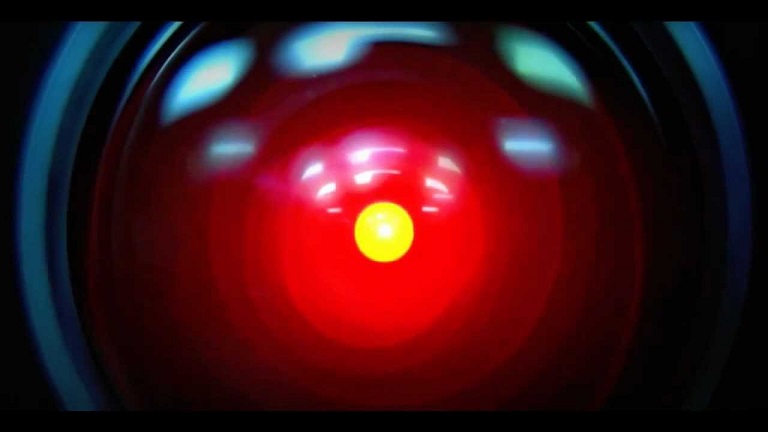

Artificial intelligence was traditionally thought of as the accumulation of many specialized programs. In Science Fiction movies, androids are good at maths and chess, because today’s computers are “good at maths”, and because they can run the “chess program”. Personally I think that computers are neither good at math or chess. Why? Because they simply do not “understand what they are doing”. It is the people who wrote the respective programs who are good at maths and chess.

But what does “understanding” mean, you ask? It seems like something only humans would be able to do. Well, a possible definition of “understanding” is the capacity to recognize abstract patterns from complex, repeated inputs, and draw conclusions from them. Let’s take a simple example. Look closely at the following:

2 + 2 = ?

Here is what just happened in your brain (provided you went to elementary school):

- “2 + 2 = ?” reaches your eyes as light. The cells in the back of your eyes are more or less stimulated in function of the amount of light they receive, just like pixels in a digital camera. The cells transmit this information to a corresponding array of neurons in your neocortex, at the back of your skull.

- This first array of neurons identifies that some of these pixels are connected together. In facts it is detecting the edges formed by digits and symbols. These neurons then pass on this information to another array of neurons. The information is now more abstract: instead of pixels, the information is passed as edges.

- This mechanism of abstraction goes on into further layers of neurons. After edges, neurons will detect shapes. At some point, the information will reach a layer that will identify the shapes as digits and symbols. Note that it does not mean that the ability of recognizing digits is built-in the human brain. No, this capacity is acquired, through a learning process. Learning is what you do when you see many times the same pattern: New synapses (= connections) are formed between neurons that fire in unison.

- If nobody ever told you what “2” means, you may recognize it as a pattern, but it will not help you decipher the equation above, just as if it was written in Chinese symbols. But most likely you did learn as a kid that “2” was in fact part of the more abstract class of “digits”, itself part of the more abstract class of “symbols”. And various symbols next to each other form another pattern that is a “mathematical expression”. With the “?” symbol (in the context of a mathematical expression) you recognize the pattern of “something that you have to solve”.

- This then triggers the pattern of “evaluating” the expression “2+2”. A computer would tackle this problem by storing “2” and “2” in memory and using the built-in addition operator of the CPU, performing the addition bit-by-bit. However a human who sees “2+2” recognizes a pattern encountered many times before, so he does not have to think hard to fire the answer “4”. Of course, if the numbers were just slightly more complex (28+17), it would take significantly more time and require a much more complex chain of activation to go on in the brain (whereas it would make no difference to the computer) …

The point is: The brain processes sensory information by recognizing abstractions in it. That is what I call “understanding”, and by that definition, machines may very well be able to understand maths and chess, provided that they learn the appropriate patterns. For chess, they would need to learn the patterns for the concepts of “games”, “winning”, “losing”, “turns”, “board”, “player”, “rules”, “pawn”, etc.. By this standard, Deep Blue is just a dump calculator.

What is interesting with Machine Learning, is that it focuses on what is possibly the most important feature of a brain: The capacity to learn. The brain wires together neurons that produce the same pattern often enough. This is how you learn chess, maths, to read, to ride a bike, etc.. In a way, the brain is much more about data than about code. Artificial Intelligence should not be about piling up tons of code. You cannot hope to anticipate each and every possible event that could occur in this world with ifs and elses.

Machine learning, and in particular Deep Learning, is rather about finding means for a machine to identify increasingly complex abstractions, make sense of raw sensory data, and generate a particular behavior. Much like a human, an intelligent machine should start in life as a baby, and grow into an adult. It is silly to try to create an adult right away.

Training an artificial intelligence with these techniques is no piece of cake, though. It takes a long time, and huge amounts of data. You can’t hope that an algorithm will recognize any car if you show it only one picture of a car (it would recognize just this one). You need to feed it many car pictures so that it detects common patterns between them. The difficulty is huge: The machine can only makes sense of the world through fixed 2D arrays of pixels. When we learn about cars, we already know of the 3-dimensionality of the world, and we can detect edges and shapes commonly.

The applications of machine learning and artificial intelligence are numerous. A common one from our daily life is the “auto-tagging” feature of Facebook photos. But these algorithms will also find applications in the physical world, in particular in robotics. Not only will robots learn to process sensory information, but they will also learn the patterns for complex movements and actions, that are not solvable with conventional methods of automatics.

Today seems a very good time to climb on the Machine Learning high-speed train, for a few reasons:

- Large amounts of structured data are more and more available from the Internet to train machine learning algorithms.

- More and more cutting-edge open-source frameworks are available to work with, and it is possible to get your questions answered very quickly (also for free).

- Large computing power is available at a minimal cost (incl. in your personal computer).

- Machine learning methods are by definition extremely generic, so they potentially apply to a vast range of problems, that are not tackled yet.

- The barrier to entry in the field is still relatively high, because few new students have the opportunity (and interest) to learn about the latest techniques that evolve quickly.

- You want to be on the right side of the computer: The one that understands how it works, not the one whose job it replaces.

The Plane-Spotting Problem

Recognizing a plane’s make and model is a tough problem, even for a human being. Nothing looks more like an airliner than another airliner. The average person probably cannot identify any model. Educated eyes will spot the recognizable ones (Boeing 747, Airbus A380), but hardly more. Only a well-trained eye can tell the differences between Airbus and Boeing aircraft.

Can you tell what this is ?

There are additional difficulties: Aircraft pictures all have a different background (clouds, airports, etc.), which has to be learnt as irrelevant. The paintings of the fuselage also have to be ignored. The algorithm must recognize the same aircraft at different positions, angles, and scales on a picture. If a recognizable part of another aircraft appears on a picture, it must be ignored too. You cannot hard-code that a particular feature is relevant, and another isn’t. The method has to “find it out” by noticing the uncorrelation between these features and the expected outputs.

As explained above, this learning process occurs by example, by feeding the algorithm with tons of labelled pictures. So the first problem is: Where to you find tons of labelled pictures?

Building a Dataset

The Internet is full of labelled pictures. All you need is a way to collect them. In my case I needed tons of aircraft pictures, associated with their make, model and airline. The obvious place to turn to was airliners.net.

Then you have to turn to web-scraping techniques, which essentially consist in telling a robot to visit webpages, to find data in the HTML code, and then follow one (or more) link from the page. For the occasion I learnt to use the Scrapy Python library, and basically coded a “crawler” doing the following:

- Perform a general search on airliners.net

- Get the data (image, make, model, etc.) for each aircraft

- Look for the “Next page” link and follow it

- Repeat from 2.

With this simple crawler, I fetched 1.7 millions of 200x133 images at a rate of approx. 500 aircraft/minute, for more than 50 hours. This is a lot of images, but that does not make a perfect dataset. In particular:

- The dataset is very heterogeneous: Some models have hundreds of thousands of pictures, while others are unique.

- Some pictures are not “what you expect”: For example you get a significant amount of in-door pictures of cockpits and cabins.

- There are some pretty strong biases susceptible to affect the training. For example, for recent models like the Dreamliner, there are too many pictures of the prototypes (with the Boeing painting). This means that the AI will wrongly associate the Boeing paint job with the 787.

- The pictures are pretty small. On one hand this makes calculations run quicker, but I fear that significant details in the pictures are just too blurry for the methods to spot them.

To cope with the first problem, I filtered the dataset to consider only a subset of seven well-represented models (A320, A330, A380, B737, B747, B777, B787), and I always used the same number of aircraft per category. I had to live with the two other problems.

OpenIMAJ: Traditional Algorithms

OpenIMAJ is an “intelligent multimedia analysis” Java library. I followed the tutorial on classification of the Caltech101 dataset. Once I got the expected results, I adapted the code to work on my aircraft pictures.

The classification is performed through a rather traditional machine-learning process: First learn to find the “interesting points” (edges, corners, etc.) in the pictures, using a SIFT extractor. Then learn to group these points together, using k-means clustering. And finally train a classifier to associate a given class to a “bag of visual words”.

I call this method “traditional”, because, unlike deep learning, it does not seek to separate multiples layers of abstraction. For this reason, it feels rather suited to perform low-level operations (like following an object in movement), but maybe less high-level analysis (like extracting the shape of a fuselage).

Nevertheless, I did obtain some results with OpenIMAJ. The training took a bit of time (about 5-7 hours to process 100000 grey-scale pictures) and yielded an average accuracy of 37.8%:

| Class | Accuracy | Error rate | Actual | Predicted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boeing 737-800 | 31.0% | 69.0% | 3575 | 2599 |

| Boeing 747-400 | 19.2% | 80.8% | 3571 | 1915 |

| Airbus a380 | 63.2% | 36.8% | 3570 | 4994 |

| Boeing 787-8 | 51.5% | 48.5% | 3571 | 5209 |

| Airbus a330-300 | 58.2% | 41.8% | 3571 | 6339 |

| Boeing 777-200 | 11.4% | 88.6% | 3571 | 1625 |

| Airbus a320 | 30.2% | 69.8% | 3571 | 2319 |

Note that the accuracy score of a random classifier for 7 classes would be of 14.3%, so this classifier is about 23% better than pure randomness… This is better than the average human, but certainly not better than an average human who would have been trained with a hundred thousand pictures.

Notice that my classifier seems to largely over-predict certain models over others. Why does this happen? No idea. This is one problem with machine learning: It is very difficult to understand the behavior that yields a particular result. This is not surprising though, as a human brain is also extremely difficult to predict.

Theano: Deep Learning & Convolutional Neural Networks

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) have existed for some time now, but they recently attracted a lot of attention after various technological breakthroughs. Thanks to the availability of very large datasets, and very powerful graphic cards (which turn out to be extremely efficient at certain mathematical operations, like convolution), they achieved a massive step of performance in image recognition challenges, as explained by one of their pioneers, Yann LeCun, now director of Facebook AI Research.

The beauty of a CNN is that it is organized in hierarchical layers, just like a brain. Various layers perform the operation of convolution, which essentially consists in “scanning” a picture to find patterns. Each pattern that is detected becomes the input of the next layer, which now looks for “patterns of patterns”.

I started working with the Python Theano deep learning framework, which makes good use of the GPU for calculations. Again, I adapted a tutorial to my particular needs.

Although the computations are performed on the GPU, it still takes many hours to fully train the network. What is especially frustrating is that you have to wait a long time before being able to try another setting, or another architecture. This makes trial & error very painful.

However, at some point I must have found a pretty effective CNN architecture, as the error rate dropped to about 21%. This architecture was finally composed of four Convolutional/Pooling layers, decreasing in size from 196x132 (the size of the pictures) down to 8x4 (the size of the highest-level feature space). For the complete details, have a peek at my script (I would highly appreciate recommendations on how to improve the current architecture).

| Class | Accuracy | Error rate | Actual | Predicted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boeing 787-8 | 76.2% | 23.8% | 1000 | 1058 |

| Airbus A380 | 74.1% | 25.9% | 1000 | 1044 |

| Airbus A320 | 84.5% | 15.5% | 1000 | 982 |

| Boeing 737-800 | 87.5% | 12.5% | 1000 | 955 |

| Airbus A330-300 | 78.2% | 21.8% | 1000 | 889 |

| Boeing 777-200 | 71.2% | 28.8% | 1000 | 1067 |

| Boeing 747-400 | 77.9% | 22.1% | 1000 | 1005 |

Again, it is pretty hard to understand exactly “what goes on inside”. Note that to help analyze their CNNs, Google engineers have recently devised a technique they called “inceptionism”, consisting in creating a sort of feedback loop inside the network to enhance the patterns each layer recognizes. The method produces amazing psychedelic pictures that could easily pass as art.

The CNN I trained can be hosted on a minimalist website, running on Amazon Web Services. Feel free to try it out, and tell me what you think!

Further Ideas

Bellow are some (rather conceptual and uneducated) thoughts on how to improve CNNs.

Beyond convolution

The convolution operation allows to scan a picture for a particular pattern. But as soon as the picture is tilted with an angle, zoomed-in or zoomed-out, the convolution quickly loses interest. The solution is for the network to learn additional tilted and scaled patterns. This seems a bit inefficient.

How about extending the convolution operation so that it integrates over an additional angular dimension, and/or scale dimension. This would make the computations much more expensive, but with the benefit of requiring less training, and less patterns kept in memory for a given object.

3D networks

What is amazing with CNNs, is how well they perform and yet how conceptually simple and abstract they are. Theano works with four-dimensional tensors to treat 2-dimensional input images. Why not add an extra dimension to the tensors and inputs? Indeed, one thing machine learning algorithms currently lack crucially is the knowledge of the third dimension. Because we (humans) live in a 3D world, we naturally learn 3D patterns. When we look at a 2D picture, we quickly infer 3D shapes from it. This may be why we require only a few examples to recognize an object, whereas CNNs need to see an object “from all angles”, requiring many more example pictures to train itself.

Of course, this means building a dataset of 3D inputs. The idea would be to train a first CNN to classify objects obtained from CAD models. You could also imagine to train the network directly with inputs coming from a 3D virtual world (possibly based on video game technology). Then, the challenge would be to connect the 2D CNN with the 3D CNN. But how do you transform a 2D pattern into a 3D pattern? If we solve this question, the benefit could be massive: It would allow to build a 3D model straight from 2D images, and, I would imagine, significantly reduce the training effort.