Scratch is a wonderful online application developed by the MIT Media Lab, that teaches kids how to make their first programs. It is very simple to use, and does not consist in boring code-typing. Millions of kids have been creating and sharing programs in the last years. Their creations are very diverse, ranging from simple animations to sophisticated video games. In fact, I first came across Scratch while searching for a visual programming environment that would be user-friendly enough to be used by engineers to describe and run complex processes.

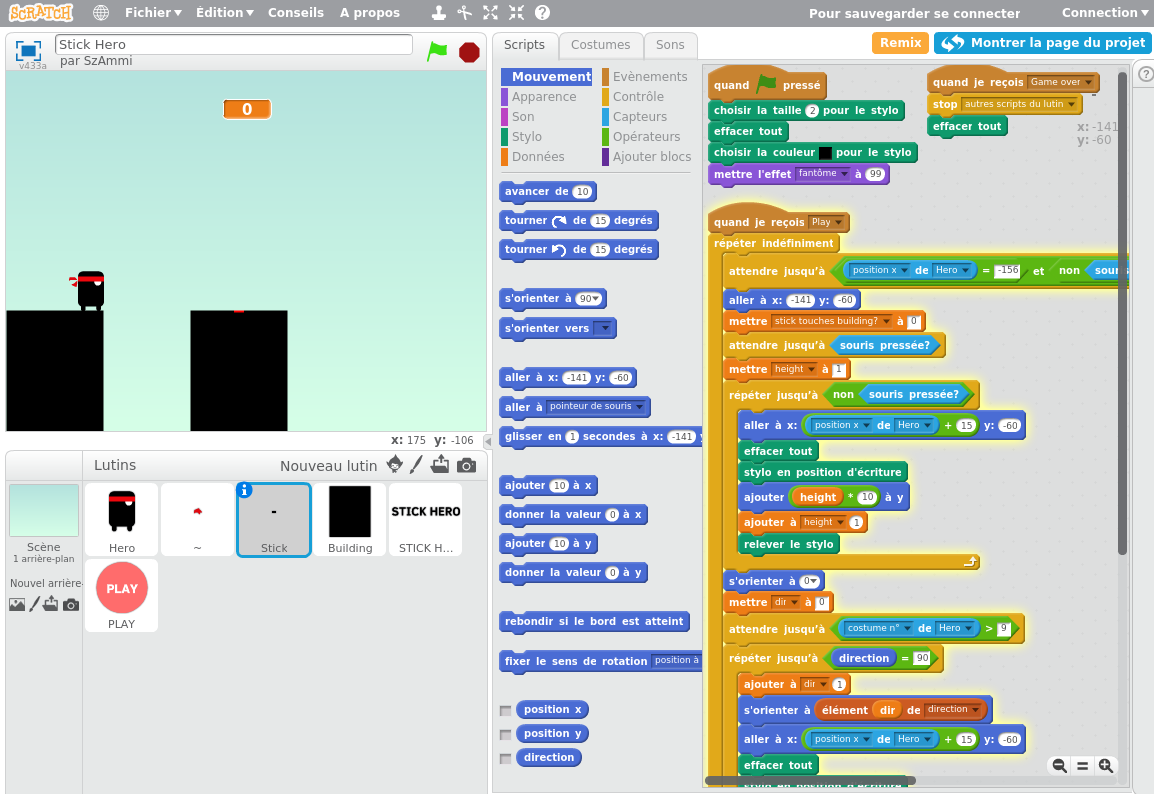

In Scratch, kids can define various objects (actual objects: shapes, pictures, characters…) and attach code to these objects. Again, “code” might not be the right word. Any possible code token (variable, function, operator, assignment, event…) comes as a block that one can drag&drop in the model. The blocks nicely fit into one another like Legos, removing any risks for syntax errors. Programs can be easily debugged by following which blocks are active in real time. The output of the program is displayed on a 2D area, which is also used for interacting with the users (responding to mouse clicks for instance).

Screenshot from MIT's Scratch: Notice the development environment on the right

Scratch is voluntarily limited in capacities and scope. It is clearly not meant for a professional use. However, it offers a number of interesting features that I think would be very useful in the context of engineering:

- It lets users create and run arbitrarily complex processes, without the need to know anything about programming.

- Users don’t get syntax errors and never have to bother about any compilation setup, or runtime environment. All you need is an Internet browser.

- Scratch is natively abstract (to some extent): It encourages users to structure their code in objects, and to create methods and routines. This is pedagogically powerful, as it naturally drags the users towards good practices.

- Scratch is extensible. Advanced users can create their own customized blocks and expose them to other users.

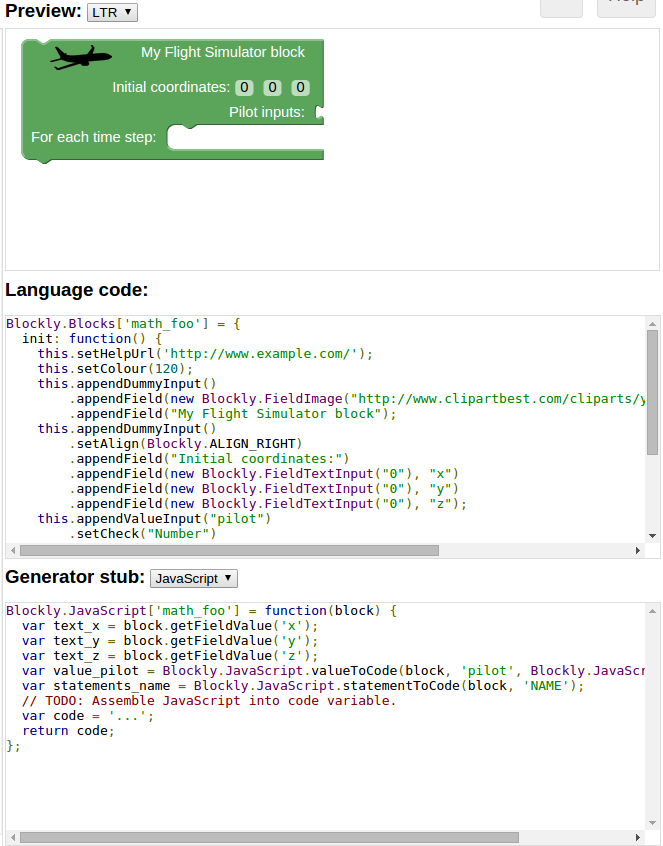

As a matter of facts, Scratch isn’t the only block language out there. Google is developing its own library called Blockly. Blockly is less famous than Scratch, but its scope is significantly bigger. The customization of blocks is a very important feature of Blockly. Users can switch from the visual blocks view to a code view. Code is generated in JavaScript or Python from the blocks definitions. This can be used to expose the API of a tool, or a web service to end users. For example, a flight simulation tool might be run using a “Fly” block, perhaps taking some input arguments (coordinates, pilot inputs) and returning some numerical outputs (e.g. a trajectory):

Conceptual use of Blockly for engineering

The beauty of this approach is that it enables specialists to generate a user-friendly, plug&play, self-explaining and self-contained block, which can be exposed to non-specialists and embedded into more complex processes. In one word, it offers perfect modularity. Being modular is sometimes a difficult requirement to comply with, but it is a must to enable various people from different departments and backgrounds to work together.

People tend to avoid to work together when this is possible. Working alone is in fact very comfortable. Working with others means you have to build interactions with them. These interactions cannot be taken for granted. They require a great effort of understanding and communication. This is especially true when these interactions involve deeply technical work, such as running or programming software. It is particularly difficult to get to know new software, and it takes a massive effort to dive into someone else’s code. As soon as two people (or more) start working together, the diversity of approaches and technologies explodes: different file formats, different programming languages, different frameworks, different conventions, etc. The more people in the loop, the more complex the interactions become.

What if you force people to expose their outbound interface as a bunch of standard blocks? Whatever technology runs behind, whatever discipline, whatever department, the “visible interface” you expose to the world is a game of Lego bricks. You are the main user of these bricks of course. But above all, the bricks are the common language you share with others. Bricks are universal and can adapt in shape and size to any domain of engineering or science.

This proposal is what I call “Serious Scratch”. It’s a framework based on an off-the-shelf block language (such as Blockly) that enables to create customized blocks that run engineering tools (in the cloud or on local machines). These blocks can be combined for various purposes:

- Chain the calculations from various tools.

- Pre-process inputs & Post-process results.

- Run tools iteratively for various design parameters (Multi-Disciplinary Optimization)

Note that a number of tools already exist for these use-cases (Isight, Modelcenter…). However, here is a couple of reasons why the approach I propose would be beneficial:

- Properly embedding tools in the existing software is particularly painful and requires very specific knowledge. This is because the current approach to tool integration is too monolithic: you embed one tool in a one-size-fits-all component (so the component has to be extremely sophisticated to adapt to any situation). The block language approach is more modular and allows to create easily and quickly dedicated blocks for each of the tools features. In fact, you break down the tool’s functions in as many atomic blocks as are required. You are then free to reassemble the tool as you feel like. This is the classic “Playmobil vs. Lego” all over again.

- Existing tools do not scale well in complexity. When you need to create a particularly sophisticated process, you have to define a huge number of parameters and map them between components. This is particularly horrible when the parameters have no structure, which is often the case (for example, an “aircraft object” is described by a flat list of a thousand parameters). Block languages offer three advantages over this approach: First, they incite users to structure the information in actual objects that consist of data and methods (something that is unusual for a non-software engineer). Second, the notion of “mapping” is replaced by the concept of assignment, as in “real” programming. Assignments are cleaner, safer and more explicit than mappings. Third, the notion of “workflow” (linear execution of components) is replaced by the execution of an assembly of blocks. This naturally opens a wide range of ways of elegantly describing a process (loops, conditional operators, routines, recursion, etc.). Again, these notions are familiar to programmers, but are completely unknown to other engineers.

Screenshot from a workflow in ModelCenter